In the remote forests on the west coast of Canada lives a mysterious ghost bear, as the local Indians called it. It was first described by Francis Kermode, which is why the bear is called Kermode (Ursus americanus kermodei).

Let's find out more about it...

To see this animal, you need to get to its habitat by seaplane or boat. This is one of the subspecies of the American black bear. And about ten percent of individuals have white or light cream colored fur!

This is not a polar bear or an albino, as one might think. Scientists believe that genetics worked this way, and the trait was fixed. In all other manifestations, it is an ordinary black bear, only white. Its dimensions can reach 1.8 meters in length and up to a meter in height at the shoulders. Males weigh up to 300 kg, females are smaller.

Like all baribals, it has a rather long muzzle, large ears (up to 8 cm) and a short tail.

The Kermode bear hunts salmon that rise to spawn. When not hungry, it eats only the caviar and head; the remains of the fish rot and serve as food for the local lush vegetation.

When the fishing season ends, it feeds mainly on plant foods: grass, mushrooms, berries, honey, although it does not disdain carrion and insects.

In the fall, it hibernates for six months; the den can be a crevice or cave in the mountains, a depression under the roots of a fallen tree. In the middle of winter, cubs weighing about 300 grams are born; by spring they grow several times larger and can follow their mother.

For the fact that these “bear spirits” still exist today, we must thank the Indians and settlers who never hunted them for their amazing white skin. Although this is a rather timid predator, which, even when wounded, does not attack, but flees.

This is how Bruce Barcott describes his encounter with this bear:

The Great Bear Rain Forest is one of the largest coastal temperate forest reserves. This wooded area is located in Canada and receives frequent light drizzle. The fish, heavy with caviar, overflows the deep rivers of the forest - a real haven for many predators. Now a clumsy figure is clumsily descending to the river bank - a black bear is going to have breakfast.

Marven Robinson noticed the bear, but remained indifferent to its appearance. “We might have better luck upstream,” Robinson says. Marven, 43, bundled from head to toe in rain gear, is a forest guide and member of the Gitgaat Indian tribe, one of fourteen tribes of the ancient Tsimshian people. The black bear is not what Marven wants to find today. He is looking for a much rarer and more revered creature - a beast that the Gitgaat Indians call "muxgmaul", a ghost bear, a walking contradiction - the polar black bear.

The ghost bear (Kermode bear) is not a hybrid, but a white variety of the North American black bear, and it lives exclusively in the forests of the west coast of Canada. Grizzly bears, black bears, wolves, wolverines, humpback whales and killer whales are found in abundance in the region, where indigenous Indian tribes have lived since time immemorial.

Marven notices a tuft of white fur caught on an alder branch. “They’re somewhere nearby, that’s for sure,” Marven says and points to the gnawed bark. “They like to stand and chew tree bark, just to let other bears know: I live here and feed on this river.”

An hour passes. Robinson and I wait patiently, perched on a moss-covered boulder. Finally, a rustling sound was heard in the bushes. A polar bear emerges from the forest cover and sits on a rock rising above the surface of the river. No, it's not pure white at all.

More like a vanilla-colored carpet that hasn't been cleaned for a long time. The bear turns its head from side to side, peering into the stream in search of fish. But before he makes an attempt to catch his prey, a black bear suddenly runs out of the forest and drives the white one away from his observation post. Although, running out is too strong a word. The bears move as if in slow motion, as if they are trying to save every calorie before the approaching hungry winter. The polar bear walks heavily away and disappears into the thicket.

Robinson has lived near ghost bears since childhood. But still, every time he meets them, he freezes, enchanted. “This polar bear is very timid,” Robinson says. “Sometimes my heart just sank.” I want to protect the albino. I once saw an old polar bear attacked by a young black animal. I was ready to rush towards them and release the entire pepper spray on the aggressor. But, fortunately, the white one reared up and threw the attacker off.” Robinson smiles, fully understanding the absurdity of a man's desire to interfere in a bear fight.

The instinct of protection is very strong among the inhabitants of the Great Bear Rain Forest. And this is one of the reasons that the ghost bear managed to survive. “Our people have never hunted polar bears,” says Helen Clifton, who we speak to in the kitchen of her home in Hartley Bay, a small fishing village. Helen, an 86-year-old woman with a strong and confident voice, is the matriarch of the Gitgaath clan. Helen says that bear meat has never been a common food for local residents. When European merchants opened a fur trading company here in the late eighteenth century, Native American hunters eagerly began supplying black bear skins. But even in those days, it was forbidden to touch a polar bear; this is a taboo - a tradition carried through many generations. “We never even talk about the ghost bear,” Helen notes.

Such silence may be one of the ancient measures to protect nature. The ban on talking about the polar bear, much less hunting it, allowed the Gitgaat and neighboring tribes to keep the very existence of the rare animal a secret from the fur traders. “I always tell young people,” continues Helen Clifton, “if you meet a ghost bear, you shouldn’t radio it to the whole world. If you want to share with someone, say that you saw muxgmola. Anyone who needs it will understand. And it will help us protect the bears.”

Even today, the Gitgaat and Kitasu-Xaixais Indians carefully monitor their charges during the hunting season. “Hunting polar bears on our land is not a good idea,” Robinson says. - It is unknown what could happen. Sometimes our fellow tribesmen may shoot back.”

The bears have had a hard time for a long time: decades of ongoing activity by poachers and trophy hunters and the operation of sawmills have led to the fact that grizzly bears have become rare in the region. But when industries closed and grizzly bear hunting was banned in some parts of the rain forest, the bears responded quickly. “When I was young, seeing a grizzly bear was a real highlight,” says Doug Stewart. As a fisheries officer, he has been monitoring fish spawning in the Great Bear Kingdom for 35 years. “And now,” Doug continues, “you see them all the time. Sometimes I see up to five grizzlies in a morning.”

They have become so prolific that experts fear that grizzly bears will push black bears, and especially the white variety of black bears, away from the best fishing spots on the river. "Where there are grizzlies, you won't see a black bear, and you won't see a white bear either," says Doug Nislos, a forest guide for the Kitasoo Xaixais Tribe. “Black bears prefer to stay away from grizzlies.”

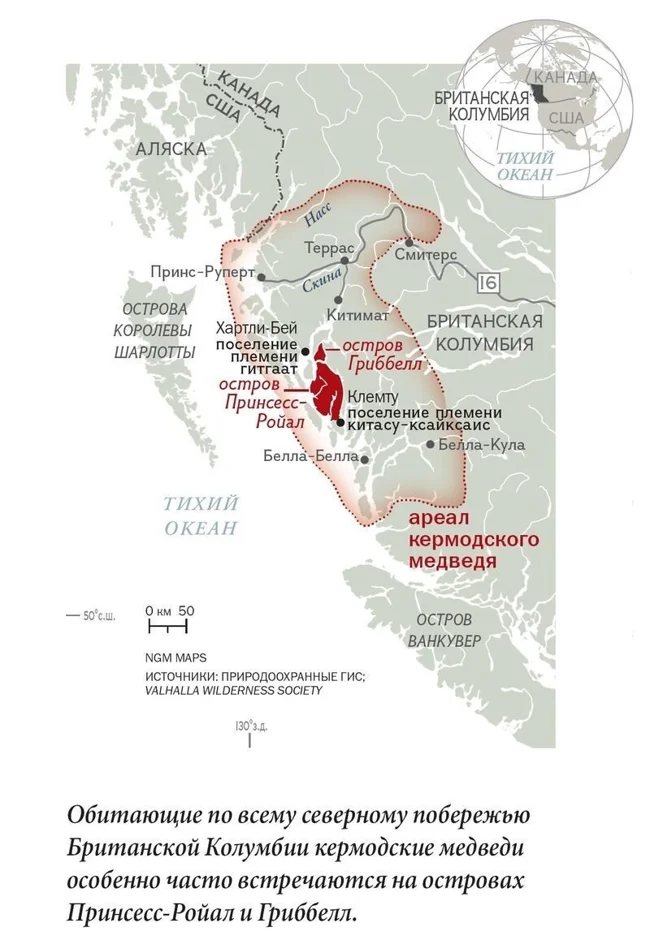

This fact gives rise to an interesting hypothesis: perhaps it was the grizzlies that provided the increased concentration of the Kermode bear gene on Gribbell and Princess Royal Islands. “Grizzlies and black bears coexist everywhere except on these small islands,” says Thomas Reimchen, a biologist at the University of Victoria. “The habitat there for grizzly bears is too limited.” They need large, grassy estuaries, subalpine meadows and extensive individual territory, which you don’t find on the islands.”

The white coloration of the Kermode bear is caused by the meeting of two recessive alleles of the MC1R gene - the same gene that is responsible for blond hair and skin in humans. To be born white, an animal must inherit one allele from each of its parents, who will not necessarily be white, they just must be carriers of a recessive trait. Therefore, it is not at all uncommon for a black couple to give birth to a white bear cub. On mainland British Columbia, white is found in one in 40 or even 100 black bears.

It is still unclear how the mutation occurred that led to the appearance of white coloring in black bears. The “glacial” hypothesis was put forward: supposedly, the white color appeared as an adaptation during the last ice age, which ended here 11 thousand years ago. At that time, most of modern British Columbia was covered in ice, and the white skin could serve as excellent camouflage.

Doug Nislos and I head to Princess Royal Island. Jumping out of the boat onto the shore near the mouth of a small river, Doug says: “Hello, bear!” As if greeting an old friend named Bear, although there is not a single animal in sight. “We don’t want to take them by surprise,” these words sound unexpected from the lips of a young 28-year-old man. He has a can of extra-strength pepper spray on his belt. Doug crunches through boulders covered with a scattering of small shells and partes the curtain of the rain forest.

We take up position under a tall hemlock tree and tighten the strings of our hoods to protect ourselves from the endless rain. Doug recently saw a polar bear here, but there is no guarantee that the bear will come here today. But we were lucky: at the beginning of the fourth, Doug points me to the opposite side of the river. A polar bear waddles along the shore. A thick layer of fat rolls under the skin of his belly. It seems that the skin is a couple of sizes too big for the clubfoot. The bear stops over a small pool, then quickly rushes into the water and - here it is, the prey: a well-fed fish about a meter long.

Recent studies have shown that the white coloration gives the ghost bear a distinct advantage when catching fish. At night, bears also get food, and then success accompanies white and black individuals equally. However, Reimchen and Dan Kinka from the University of Victoria noted that during the daytime the number of successful attempts between white and black relatives is different: polar bears manage to catch a fish in one of three attempts, and black bears manage to catch a fish in one out of four. “Light objects visible through the surface of the water are less likely to deter fish,” suggests Reimchen. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why such a feature as white coat color has survived to this day. Salmon fish are the main source of fat and protein for coastal bears, so a lucky female can store more fat during the winter, potentially increasing the number of cubs she will produce.

Princess Royal Island is still in the grip of rain as Doug Nislaus and I watch a ghost bear feast. When there is a lot of prey, bears become picky. Some people only eat fish heads. Others rip open the bellies of the fish and suck out the eggs. Still others turn into gluttons and try to eat as much fish as possible. “I once saw a ghost bear eat 80 salmon in one sitting,” smiles Nislos. But our bear has his own trick: he prefers to dine alone. Clubfoot takes the fish in his teeth and goes up the hillside to look for a more secluded place. About twenty minutes later he returns, catches another fish and takes it back into the forest. This continues for several hours until night falls on the island - and we leave our observation post.

0 comments