Harry Harrison and the Tao of Kolobok - about the life and books of the writer (18 photos)

American science fiction writer Harry Harrison gained cult status back in 1972, when a translation of his “The Indomitable Planet” was published in the magazine Around the World. However, in his native West, Garrison’s career was not easy - it was, oddly enough, hindered by the fact that the writer was too versatile.

One blogger wrote the following post on the day of Harrison's death - August 15, 2012:

I read the obituaries of G. Garrison, compiled by the loving hands of his fans. The obituary outline is straightforward. First sentence: the great G. Harrison has died. Second sentence: a man who wrote many books, of which I liked two, but seventy-three - no, I didn’t like...

Let's not be indignant: the joke is good, and Harrison himself loved to laugh. And most importantly, there is a fair amount of truth in this joke: there is hardly a person who would like all of Harrison’s books. In order to gain his own fandom, Harrison knew too much. In some ways he was like his hero, Slippery Jim DiGris. Or Kolobok, who eluded everyone who tried to appropriate him.

Kolobok's Path has its advantages, but it is not the Road of Glory. Rather, the Road to Freedom: get out of all traps, overcome all temptations - and have the last laugh.

Iconoclast of the Universe

In English there is a verb “pigeon-hole” - “to put into categories”, “to classify”. So, “pigeonholing” Harrison has always been difficult, no matter how you approach it. Take nationality for example. It would seem that an “American science fiction writer” with a name could not be more Anglo-Saxon (Harry, Harry’s son!).

In fact, he is Henry Maxwell Dempsey, a descendant, on the one hand, of Spanish Jews who settled in Latvia and later moved to St. Petersburg, and on the other, of Irish emigrants. Considering that from the age of thirty Harrison lived outside his native America, mostly in Europe, it is fair to call him a European writer. Or better yet, just a writer, without connection to the country and people.

With the bibliography it’s exactly the same... I want to write “trouble”, but this, of course, depends on how you look at it. Many of Garrison's science fiction colleagues have an underlying theme or characteristic that unites their work. Sheckley gravitated towards absurd humor. Zelazny wrote about supermen rebelling against the world order. Vonnegut was glorified by his “telegraphic-schizophrenic” style, Bradbury by his poetic style, Moorcock’s hero is an incarnation of the Eternal Warrior, and so on. And Harrison? Try to tell me what is typical for his work.

It was easier in Soviet times: the collection “Training Flight” (1970) allowed him to be labeled as the author of humorous fiction. The main part of the collection was occupied by the funny “Fantastic Saga”, in which Hollywood uses a time machine to make a film about real Vikings. When The Indomitable Planet was translated, there was reason to think that Garrison specialized in sci-fi action films. The wild planet Pyrrhus, where all living things are for some unknown reason hostile to people, a hero with the pseudo-aristocratic name Jason din Alt, burdened not only with muscles, but also with brains... Such action films were rare in the USSR, and Harrison was remembered.

It was all the more interesting to read during the years of perestroika novels about the Steel Rat, which have almost nothing in common with books about Jason din Alta (except perhaps for the pseudo-aristocratic name of Jim di Grisa). And when it came to “Move over! Move over!” and West of Eden, it became clear that there was simply no “typical Harrison”.

Writer's freedom is a wonderful thing: write what you want, without looking back. The general reader, however, loves that the author can be labeled. And if there is no label, interest in the writer wanes. And so it happened. In the West, the death of Harry Harrison did not go unnoticed, but the young fandom hardly reacted to it. But half a century ago, in 1967, British science fiction writer Brian Aldiss, the leading representative of the New Wave, wrote in a letter to Harrison:

Really, Harry, I think I hate fiction... I tried to avoid this conclusion, but I wouldn't care if the whole operation went to waste, except for you, Blish, Ballard, Dick - but who else?

Imagine - Harrison is on a par with Philip K. Dick! And this is not a joke or a friendly nod: Dick himself called Harrison “the iconoclast of the universe,” the subverter of inflated authorities. Nowadays, Dick, Aldiss, and Ballard are considered cult authors in the West - unlike Harrison, although his work is more diverse and less elitist. Paradox!

Harry Garrison (right) with old friend Brian Aldiss (center) and science fiction writer Greg Beer.

Antihero of the American Army

In part, Garrison’s writing destiny is a derivative of his life, which cannot be called easy. It’s not that it was full of disasters—God had mercy. But money was tight for the Harrison family. Until the mid-1980s, Garrison was often in debt, although he published a novel a year. The writer later said in an interview with Neil Gaiman:

I dreamed of earning as much as an elevator operator at the publishing house that published my books. It took fifteen years to make this dream a reality.

The rest of his biography seems smooth. But if you take a closer look, it turns out that Harrison's path is a path of missed opportunities. It’s not that he missed them out of thoughtlessness or laziness. At times, success was hampered by the eternal desire to change places, sometimes by the banal “not fate.” A good example is one of the writer’s most underrated novels, Bill the Galactic Hero.

From a young age, Harrison was fond of science fiction and drawing; he thought for a long time about what to become, and was inclined towards art. But at the age of eighteen he was taken (or rather, shaved) into the American army.

My generation turned out to be a generation of conscripts; we needed to successfully finish not college, but the war.

The year was 1943. Harrison only indirectly participated in the only war that he later called “just,” World War II. But the shock of the army remained with the writer forever. Even many decades later, he never tired of repeating: you need to be in the army to understand and hate the military; the army is a fascist state that defends a democratic state.

Military service “hurt” Harrison so much that he carried his hatred of military order and war throughout his life. Even in Donald Wollheim's anthology Men on the Moon (1969), Garrison wrote less about the Moon than about the Vietnam War, which "devastated us all" in the introduction to his story:

A picture of the Earth as seen from the Moon should hang on the wall of every schoolroom and home in the world. We see a lot of clouds and water and very little land. The borders between countries are not visible at all.

During my military service, I acquired many valuable professions and skills. He rose to the rank of sergeant, was a small arms instructor, drove a truck, looked after an ammunition depot, and became a turret control specialist. When I was assigned to escort those placed in the guardhouse, I learned to click menacingly with a carbine. And he gained considerable experience in many equally useful matters.

I left the army having completely adapted to it. However, it turned out that it did not prepare me at all for returning to real life. I was never able to fit smoothly into the only role that I learned in civilian life - the role of a child.

Of course, prisoner of war Kurt Vonnegut, who went through the fiery hell of Dresden, had it much worse. As did Joe Haldeman, who was seriously wounded in the Vietnam War. And Joseph Heller, the pilot of the B-25 flying fortress, could tell much more about the army than Harrison. Each of these writers, like Harrison, wrote a funny and scary novel that reflected his experiences in the army. And if you look at it objectively, permeated with the most caustic anti-war pathos, “Bill the Hero of the Galaxy,” in which a simple guy is broken through the knee by the space army, is no weaker than Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five,” Haldeman’s “Infinity War,” or even Heller’s “Catch-22” ( with which “Bill” was compared at one time by smart critics).

And the result? The books of Vonnegut, Haldeman, and Heller are considered their main creations and are studied at universities. “Bill” has no chance of doing anything like this, although it is, among other things, also a parody novel - of bad science fiction and Robert Heinlein’s militaristic “Starship Troopers” (for this, Heinlein was so offended by Harrison that he stopped talking to him). Ultimately, The Bill was only good enough to produce six sequels with various co-writers, including Robert Sheckley and David Bischoff.

Illustration by Keith Parkinson for the novel “Bill the Galactic Hero”

Literary project “I Ate a Pygmy”

After the army, having beaten his thumbs for a year, Harrison entered art school. There he found something to do that combined drawing and fiction: he began to compose, edit, draw and layout comics. Many famous science fiction writers started with this, but even here Harrison was unlucky. The comics were not so great (at least they didn’t leave a trace in history), and there was always a shortage of money. That's why, after making his debut in 1951 with the story "Rock Penetrator" in Worlds Beyond (ironically, this was his last issue), Garrison published only two stories over the next five years.

All this time he worked like an ox to provide for himself and his family. I had to work not only with comics, but also with “confessional journals.” There was this type of publication in the USA - confession magazines, designed for proletarian women. “Revelations” of female readers were published there, based on the formula “sinned, suffered, repented.” Harrison wrote articles in these magazines such as “I Ate a Pygmy” and “I Cut Off My Arm.”

It got to the point of absurdity: the future Grandmaster labored as “Aunt Harriet,” who helped readers of the comic book magazine deal with problems. The magazine was called Runchland Romances - roughly translated as "Cattleman's Love Stories."

Can you imagine what kind of people wrote about problems in this magazine? "Dear Aunt Harriet, I'm pregnant, I'm fifteen, I haven't told anyone..."

And only in the mid-1950s, having moved from New York to Mexico City, Garrison began to write fiction, as his soul demanded. In November 1956, Fantastic Universe magazine published “The Unemployed Robot,” which marked the beginning of a series of stories that were later included in the collection “War with Robots.” In August 1957, Astounding published the story "The Steel Rat", in which Jim diGriz made his first appearance.

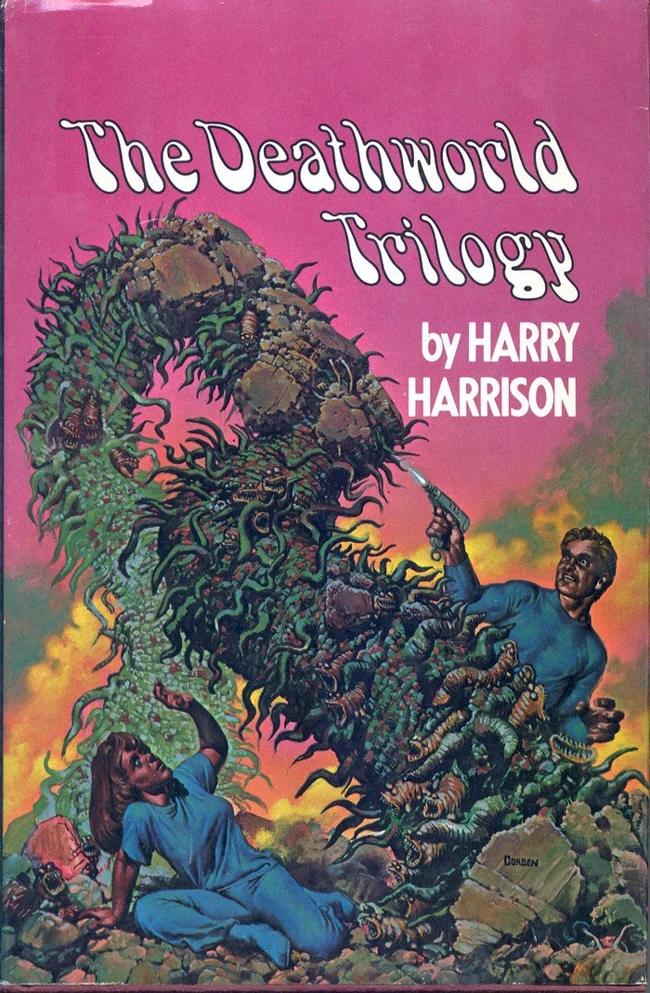

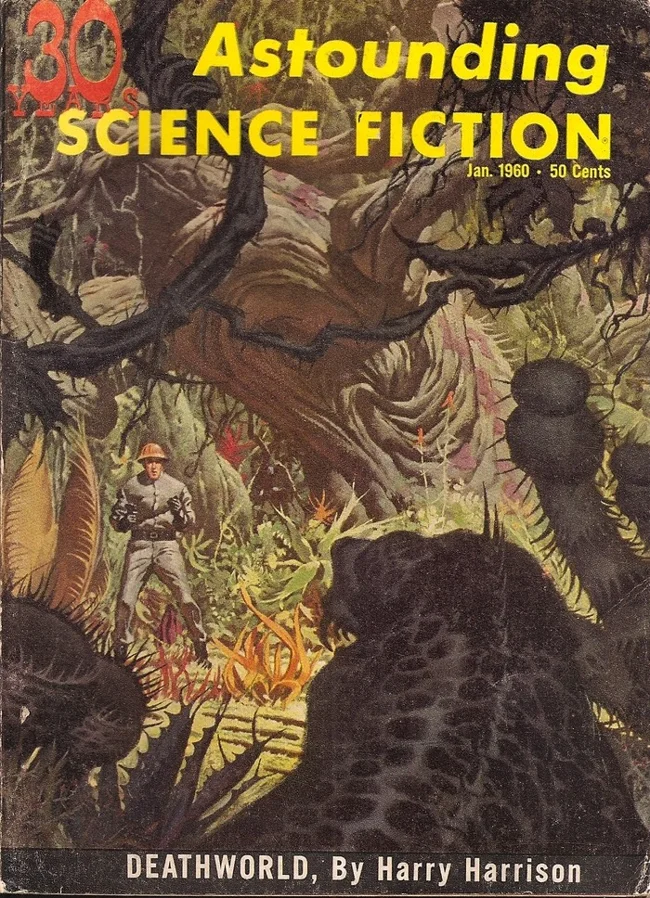

The writer devoted the next three years to working on a sci-fi action movie - and in 1960, “The World of Death” was published in three issues of Astounding. The novel became a kind of manifesto: Harrison believed that this magazine, edited by the legendary John Campbell, published empty texts, and wanted to prove that he could write something much more interesting.

The Death World trilogy, one of Harrison's main works.

Since the mid-1950s, the Harrisons could not sit still: in total they visited sixty countries, and lived for a long time in “nine or ten”. Mexico, Great Britain, Italy, Denmark (“We came there on a private visit, and stayed for seven years”), Ireland... Harrison was proud that he spoke nine languages decently, and could order beer in sixteen. One of his favorite languages was Esperanto; Garrison was an honorary patron of the World Esperanto Association and the first science fiction writer to write a story in Esperanto.

However, in the early sixties he was not thinking about linguistics, but about finance. Later, he recalled how his family, once in Italy, was starving: the literary agent stopped sending Harrison money, and he was left with one hundred lire, with which he could buy a liter of milk for a child - or a stamp for an envelope to again ask the agent to send money. The money went towards the stamp because the milk was sold on credit. Salvation came from an unexpected direction: Harrison was offered to write comic book scripts about Flash Gordon, which he did for ten years.

On both sides of the litfront

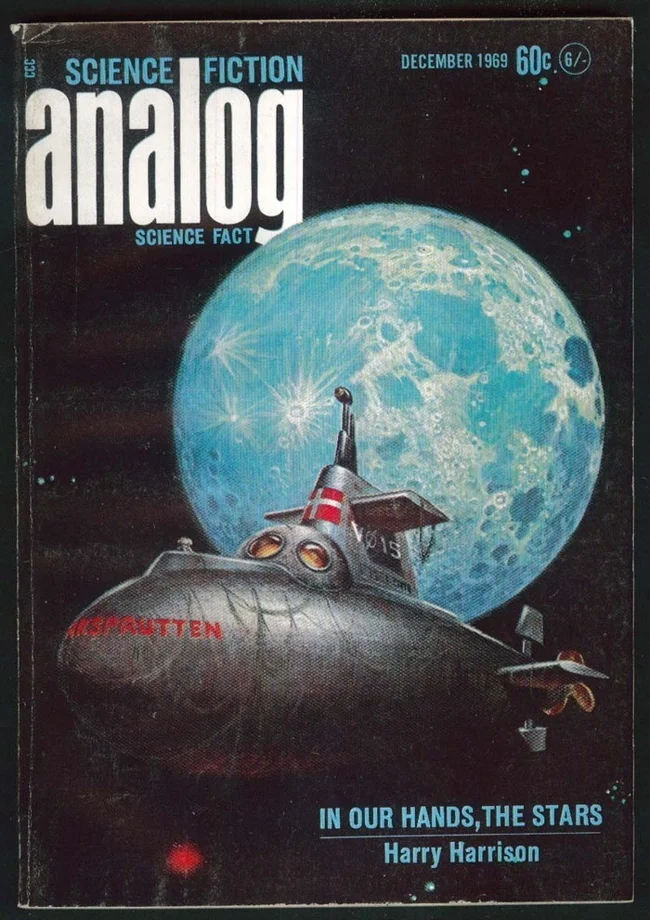

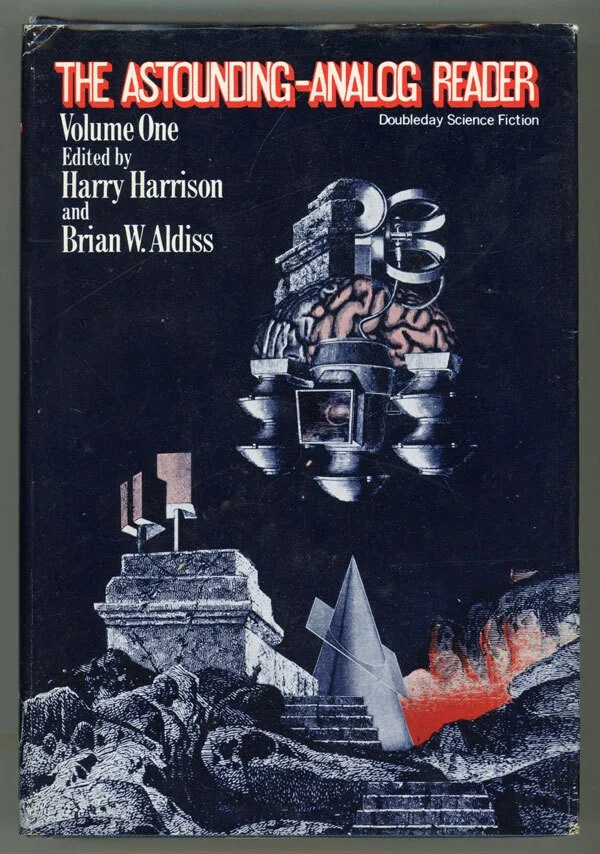

At the same time, Harry Harrison was far from the last writer of his generation. On the contrary, in the 1960s he was considered one of the most promising science fiction writers, and all for the same reason: he could write (and wrote) anything. The turning point decade for Western science fiction was marked by the struggle between the Old Guard and the New Wave. The commander of the Old Guard remained John Campbell, editor of Astounding magazine, later renamed Analog. The leader of the New Wave was Michael Moorcock, editor of New Worlds magazine.

Harrison managed to fit into both movements at the same time, which no one else could do. On the one hand, together with Robert Silverberg and Frank Herbert, he was one of the main authors of Analog, on the other, the same “Bill the Hero of the Galaxy” was first published in 1965 by New Worlds. Harrison's position was unique, but he did not benefit from it.

The writer did not intend to go to the barricades. Although I could easily. In the story "Streets of Ashkelon" (1962), he made the hero an atheist who tries to protect aliens from a zealous Christian missionary. In those days, religion in SF was a taboo topic, and the story was not published for a long time. If Harrison had developed his success, he would have earned a reputation as an iconoclast in wide circles, as did Philip José Farmer (stories about Father Carmody) and the same Moorcock (Behold the Man), but alas.

Or again: in the essay “We Sit on Our...” (1964), Garrison wrote sarcastically that science fiction writers habitually self-censor their texts, purging “sex and bodily functions” from them, and would not be able to correct themselves even if they wanted to. This remark remained a remark - the writer left the task of crushing the taboo to his colleagues, and he himself continued to write Puritan works. Only much later, in 1977, he published the book “Giant Eggs of Fire: A History of Sex in Science Fiction Illustrations.”

Harrison has had the chance to steer the literary process more than once. As you know, the New Wave began when editor John Carnell handed New Worlds magazine over to Moorcock. Carnell entrusted his second magazine, Science Fantasy, to the writer Cyril Bonfiglioli. He renamed the publication SF Impulse, quickly lost readers and at the end of 1966 left the magazine to Ballard, who handed it over to Garrison. But it so happened that Harrison had to urgently leave England; formally remaining the head of the editorial office, he transferred his responsibilities to the shoulders of science fiction writer Keith Roberts. In March 1967, SF Impulse died.

One inevitably wonders: could Harrison, having his own magazine, become one of the leaders of the New Wave? Surely he could - at least as an editor. He had excellent literary flair; it was he who bought the first story from the legendary James Tiptree Jr. And Harrison had enough courage: let’s say, in 1954, as the editor of a little-known science fiction magazine, he accepted for publication Damon Knight’s story Rule Golden, which was rejected by other publications for ideological reasons: it could be regarded as an attack against Senator McCarthy, who launched a hunt for communist “witches”.

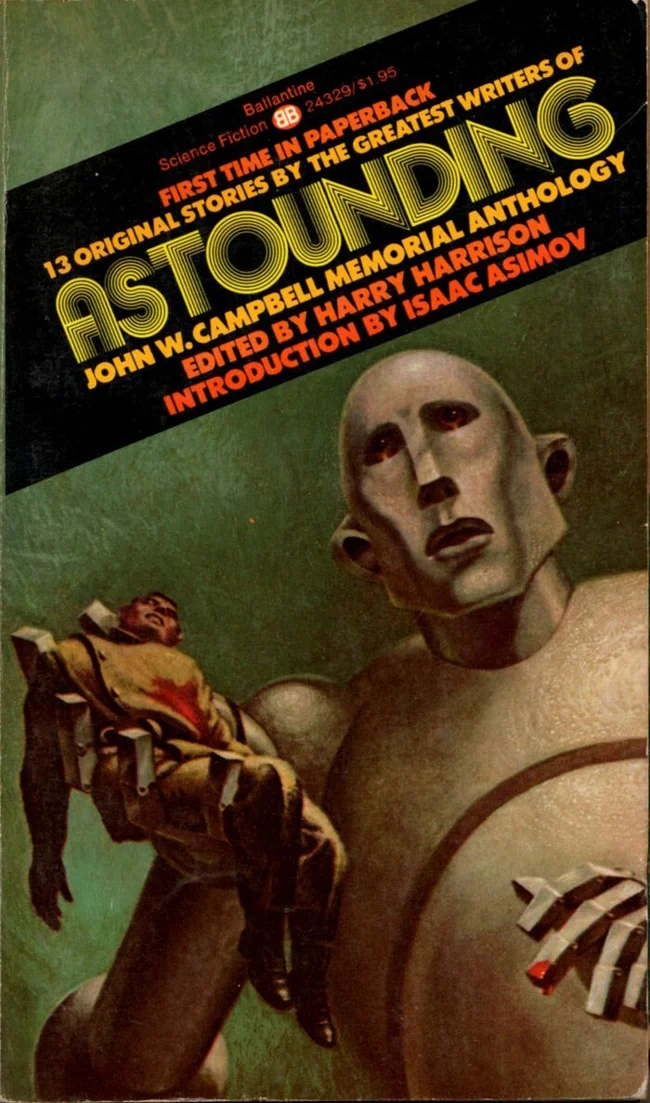

A few years after the SF Impulse story, Garrison rejected the offer of Campbell, who, shortly before his death, offered the science fiction writer his position as editor of Analog, a stronghold of the Old Guard. Garrison did not want to move to New York and believed that Campbell was irreplaceable. By the way, one of Garrison's best books, Lifeboat, written together with Gordon R. Dixon, was invented by a science fiction duo together with Campbell. This brainstorming session was captured on film by their colleague James Gunn.

Long live the inter-genre tunnel!

So it turned out that, by practicing the Tao of Kolobok, Harry Harrison left both the New Wave and the Old Guard. What did he exchange his place in the literary pantheon for? For books. Those that he wanted to write, and that no one but him would have written. Brian Aldiss said that Garrison is one of the few authors who managed to bring the “former power” of science fiction into a new era. Already in his first novels, “The Indomitable Planet” and “Planet of the Damned,” one could feel “a natural and proper despair that endowed all other existence with joy.” It was hidden behind the guise of humor - just like Sheckley and Bester. But Harrison could do a lot more than his colleagues, and he wrote not only funny things. So he didn’t get the title of the first SF satirist either. And yet, if we define the three pillars on which his work stands, humor will be the first.

In my opinion, science fiction is literally made for humor. And if there aren’t enough funny science fiction books, it’s because it’s very difficult to write them well... I would like readers to relax and have fun, distract themselves from reality and improve their digestion and mood with the help of a giggle, or even a loud animal laughter...

In this he succeeded, composing many funny stories. First of all, ten books about the Steel Rat, which brought Harrison twice as much money as all the other novels combined. The writer adored his Jim di Grisa, and for good reason. This hero is good because he can be launched into any conventional labyrinth - even into the army (“The Steel Rat is going to the army”), even into politics (“The Steel Rat is going to the presidency!”), even under the big top of the circus (“The Steel Rat is going to playpen"). Harrison himself considered the best book “The Steel Rat Needs You!” — he wrote it “as if from the subconscious” and laughed out loud at the same time. It’s no wonder that the plan to stop at three, six or eight books about the space scoundrel collapsed: the science fiction writer wrote the epic about Di Gris almost until his death.

The Steel Rat, Jim di Griz, also became the hero of comics published in the magazine 2000 A.D. - Judge Dredd is from the same place.

On the back of the same whale is the step of Bill, the hero of the Galaxy, who not only carries an anti-war message, but also parodies militaristic space operas. In 1973, Garrison thoroughly dealt with space operas by writing the novel “Star Adventures of the Galaxy Rangers,” where the universe is ruled by cockroaches, and two brave men end up as a homosexual couple. The “Fantastic Saga” stands apart with its filmmakers, who, not caring about the “butterfly effect”, went back in time to make a film about the Vikings. Behind this novel one can already see the back of the second whale - alternative history.

When people say “alternate history,” they usually mean books like Dick's The Man in the High Castle or Keith Roberts' Pavane. Harrison is again remembered last, although he wrote perhaps more novels in this genre than any other famous science fiction writer. Among Harrison's alternatives is the wonderful trilogy "Eden" about a world where dinosaurs did not go extinct, but evolved and created a civilization that is not similar to humans. Harrison came up with the first book, “West of Eden,” for several years, consulting with “professors who secretly read SF” - biologists, paleontologists, linguists (the techno-thriller “Turing Selection” was also later written, co-authored by an artificial intelligence specialist Marvin Minsky).

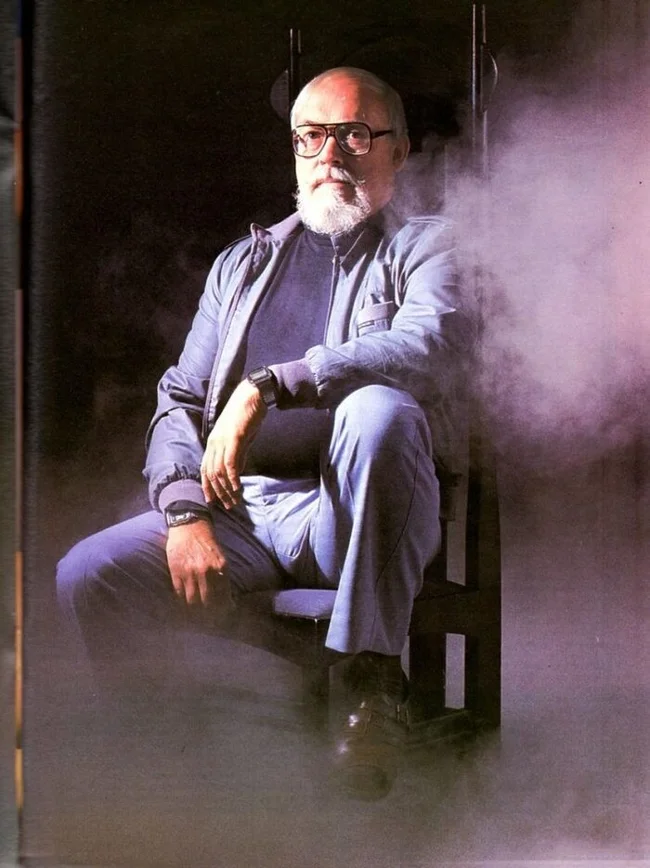

At the peak of his career, Garrison posed for Knave magazine, where his interview with Neil Gaiman appeared

In the early 1980s, Harrison could already afford this. This was the peak of his literary career: three dozen books, the circulation of which was constantly being reprinted, “enough money to live for three or four years without writing a novel a year.” Both the author himself and his publishers, who released the book as a future bestseller, with a huge advertising budget, placed a big bet on West of Eden. Alas, hopes were not justified - in the era of cyberpunk, intelligent dinosaurs did not interest the public.

Harrison's most famous alternative book remains the book “Long Live the Transatlantic Tunnel! Hooray!" (1972) is a wonderful novel about a world where the Moors won the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, there was no Spain, Columbus did not discover America, and in 1973 the world is still ruled by the British Empire, on which the sun never sets. The main character is a descendant of George Washington, who was executed for treason. The plot revolves around the construction of a tunnel between continents, which the British are undertaking on the advice of Lord Keynes in order to boost the economy during the next crisis.

“The Tunnel” can be called not only alternative history, but also a forerunner of steampunk and social science fiction. This is the third whale of Harry Harrison, and it is worth talking about it in particular.

America could be the light of the world

In one interview, the science fiction writer said:

I'm surprised by my success outside the US. I don't understand why people read me in other countries. It seemed to me that my allusions to the history and modernity of the United States were understandable only to Americans.

It's true. We, foreign readers, do not perceive the context of Garrison’s books, which is why almost their main message passes us by. Perhaps it will also miss modern American readers - Garrison, like his colleagues in the New Wave, spoke about the present in veiled ways.

Harrison's multi-volume books have been published many times in our country. Polaris publishing house published more than twenty volumes in the “Worlds of Harry Harrison” series back in the first half of the nineties. Then there was the “Steel Rat” series, and finally a thick sixteen-volume edition of “The Whole Harrison” was published by the Eksmo publishing house.

"Tunnel" is a great example of this. In 1973, the West faced a severe economic crisis, but decided to get out of it not using Keynes’s methods, but in a completely different way. In this sense, Garrison's novel is a frank political-economic treatise wrapped in fiction. This, however, few people understood.

Similarly, Harrison's final trilogy, The Star Spangled Banner (1998-2002), is another alternate history, somewhat inverse to The Tunnel (Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, dies in the midst of the British-American crisis, the British attack USA, and instead of a Civil War, the Yankees liberate Canada and Ireland and then take over Great Britain) is essentially a commentary on what was happening in America in the 1990s. Harrison wanted to show and prove:

The US Constitution is the most accurate document in the world. We must follow it... I look at my homeland with despair. America could be the light of the world...

Garrison's best-known social science fiction novel is the Malthusian nightmare Move Over! Move over!” (1966) about the monstrously overpopulated New York of 1999, where 35 million people live and food riots break out daily (a similar outcome was predicted by the scientist Thomas Malthus, realizing that the amount of food was growing in arithmetic progression, and the population - in geometric progression). Harrison spent six years writing this book, studying research on overpopulation and ecology with his characteristic meticulousness.

Richard Fleischer's film adaptation of Soylent Green (1973) added to the popularity of the novel, with which Garrison, however, was dissatisfied. The fact is that the director decided to add “spice” to the plot: the heroes found out that a universal food called “Soylent” is made from human corpses. There was no cannibalism in Garrison's book; The word "Soylent" is made up of the English words "soya beans" and "lentils", that is, "soybeans" and "lentils".

Soylent Green, a classic Hollywood dystopia. Ironically, most people remember the very idea from this film that was not in the book.

Garrison’s relationship with Hollywood did not work out at all, although the rights to film adaptations of “The Fantastic Saga,” “The Steel Rat” and “Bill” were acquired by the studios a long time ago. Maybe because Garrison insisted on an important point in the contract: on the first day of filming, he should be given one hundred thousand dollars. One way or another, the science fiction writer did not like modern Hollywood and disdained Star Wars, although his Indomitable Planet invested in the development of such “space westerns.”

Garrison generally hated fantasy fairy tales, calling them “the school of tears and tampax - I mean all sorts of dragons and snakes of dreams” (we are talking about Vonda McIntyre’s novel “The Snake of Dreams”). The writer called the “Hammer and Cross” trilogy, which takes place in the early Middle Ages, “historical fantasy.”

The mysterious "John Holm", Garrison's co-author, is renowned Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey.

Grumpy bratty grump

Harrison loved, as you might guess, “hard” SF. He even came up with “Harrison’s Law,” which states: the core of fiction is science fiction, and without the core there will be no periphery. Among SF writers in the mid-1980s, Garrison singled out Gregory Benford, and considered the rest to be insufficiently skilled. About Jeremy Pournelle he said that although he writes SF, he doesn’t know how to write, about Larry Niven - that he only thinks he writes SF, and he himself couldn’t even get a bachelor’s degree... Of the Englishmen, Harrison respected only Brian Aldiss and was not shy at all say about bad writers that they are shit.

Any literary groups frightened him, reminding him of the army; Garrison once said about the famous sci-fi seminar at Clarion, whose graduates included many science fiction writers, including Kim Stanley Robinson, Bruce Sterling and Cory Doctorow:

Looks like an army camp. If you cannot live without fascist methods, if you like being intimidated, you will like it.

With SCI FI Magazine editor Scott Edelman.

As fate would have it, Garrison's years of popularity coincided with an era when Western SF was rapidly becoming a mass consumer product. He complained:

Too much science fiction is being published now. Six books a week instead of six books a month... It's too easy to write fantasy - and very difficult to write science fiction. So it turns out that we have boring writers who write boring books for boring readers.

This is said about America in 1984, but if you remember how many science fiction books (and what kind) are being published in recent years, Garrison’s pessimism turns out to be infectious.

There used to be a fighting spirit. But today publishers don't care. And the writers don't care. Only readers care - but they always care...

By 1990, the science fiction writer was forced to change his opinion about readers:

Ignorant, tongue-tied, incompetent writers sell texts to undemanding editors, and the stupid masses of readers don’t give a damn about all this.

Harry Harrison.

After Harrison's death, his admirer Neil Gaiman wrote on his blog: "He was a grumpy, willful grump, and a pleasure to communicate with." And among his contemporaries, Harry Harrison was a phenomenon, and now, when both the Old Guard and the New Wave are gone and have become almost indistinguishable against the backdrop of fantastic consumer goods, there are almost no figures like him left. “They don’t make things like that anymore today.”

We have forgotten the Tao of Kolobok, we have forgotten that you can remain yourself only if you refuse to compromise, remaining faithful to the principles of writing. The Road of Glory is dearer to us than the Road of Freedom, but the stocky, white-bearded American looks at us with condemnation - and perhaps this will be enough for some. Gaiman writes: "If you like sci-fi, you've definitely read one of Garrison's books." Isn't this a reward?

Harrison's advice to aspiring writers

Forget it, boy! Well, if I haven’t forgotten, print only on one side of the sheet, double-spaced.

But seriously: if you want to write SF, read all of SF so you know what they did before you. Then read the mainstream so you know how to write. 99 percent of all famous science fiction writers (Brian Aldiss is a remarkable exception) write not even crap - worse than crap!

Writing is one of those activities that requires long and hard work. You need to work as hard as, say, a neurosurgeon works. No one will tell you exactly how to write: if you write well, you write well, if not, you sit with your butt in a puddle.

Fiction by Harry Harrison

World of death

"The Untamed Planet" (1960)

"Ethicist" (1963)

"Horse Barbarians" (1968)

Steel Rat

"Birth of the Steel Rat" (1985)

"Steel Rat Joins the Army" (1987)

"The Steel Rat Sings the Blues" (1994)

"Steel Rat" (1961)

"Revenge of the Steel Rat" (1970)

"Steel Rat Saves the World" (1972)

"The Steel Rat Needs You" (1978)

“Steel Rat for President!” (1982)

"Steel Rat Goes to Hell" (1996)

"Steel Rat in the Playpen" (1998)

"The New Adventures of the Steel Rat" (2010)

Brian Brand

"Planet of the Damned" (1961)

"Planet of No Return" (1981)

Bill - hero of the galaxy

"Bill the Hero of the Galaxy" (1965)

"BGG on the Planet of Robot Slaves" (1989)

"BGG on the Planet of Blocked Brains" (1990), with Robert Sheckley

"BGG on the Planet of Unknown Delights" (1991), with David Bischoff

"BGG on the Planet of the Zombie Vampires" (1991), with Jack Haldeman II

"BGG on the Planet of Ten Thousand Bars" (1991), with David Bischoff

"BGG: The Last Ill-Fated Adventure" (1992), with David Harris

Eden

"West of Eden (1984)

"Winter in Eden" (1986)

"Return to Eden" (1988)

Hammer and cross

"Hammer and Cross" (1993), with Jon Holm

"The Cross and the King" (1994), with John Holm

"The King and the Emperor" (1996), with John Holm

Star Spangled Banner

"Anaconda Rings" (1998)

"Enemy at the Door" (2000)

"In the Lion's Den" (2002)

To the stars

"The World of the Motherland" (1980)

"World on Wheels" (1981)

"Return to the Stars" (1981)

Single novels

"Plague from Outer Space" (1965)

“Move over! Move over!” (1966)

"Fantastic Saga" (1967)

"Captured Universe" (1969)

"Spaceship Doctor" (1969)

"Daleth Effect" (1970)

“Long live the Transatlantic Tunnel! Hooray!" (1972)

"Stonehenge" (1972)

"Star Adventures of the Galaxy Rangers" (1973)

"Shooting Star" (1976)

"Rescue Ship" (1976), with Gordon R. Dixon

"Invasion Target: Earth" (1982)

"Time for a Rebel" (1983)

"Turing Selection" (1992), with Marvin Minsky