10 cool engineering tricks that the Romans taught us (11 photos)

The ancient Romans were good at some things, but not at others. As far as abstract sciences and literature are concerned, they have always been in the shadow of their Greek neighbors. Their poetry never reached great heights, their philosophies of Stoicism and Epicureanism were borrowed, and anyone who has ever used Roman numerals knows how difficult the system was even for simple arithmetic.

If you wanted someone to explain geometry, you would have to look to a Greek. If you wanted someone to build you a floating bridge, a sewer network, or a weapon that could shoot flaming balls of gravel and tar over 270 meters, you'd look to the Roman. What the Greeks gave us were the brilliant architectural, organizational and engineering achievements of Rome that set it apart from the ancient peoples. Even though their knowledge of mathematics was rudimentary, they designed models, experimented, and built as tightly as possible to compensate for their inability to calculate load and weight. The result was a complex of buildings and architectural structures, from the Limira Bridge in Turkey to Hadrian's Wall in the United Kingdom.

With so many brilliant examples, many of which are still in excellent condition, it's hard not to learn a few lessons about how to create designs that last.

In this article we will look at the 10 coolest engineering achievements of Rome.

Dome

Our huge vaulted arches, huge atriums (by the way, a Latin word), hollow steel and glass skyscrapers, and even a simple high school gymnasium - all these structures were unthinkable in the ancient world.

Before the Romans perfected domed construction, even the best architects had to deal with the problem of a heavy stone roof, littering temples and public buildings with columns and load-bearing walls. Even the greatest architectural structures - the Parthenon and the pyramids - were much more impressive from the outside. It was a dark, enclosed space inside.

Dome of the Pantheon in Rome

Roman domes, on the other hand, were spacious, open, and for the first time in history created a real sense of interior space. Based on the realization that the principles of the arch could be rotated in three dimensions to create a shape with the same supporting force but an even larger area, dome technology was bolstered by the presence of concrete, another Roman innovation that we will discuss later in this article. This substance was poured into molds on wooden scaffolds, leaving behind a hard and durable shell of the dome.

Siege Warfare

Like many technologies, Roman siege weapons were primarily developed by the Greeks and then improved by the Romans. Ballistae, essentially giant crossbows that could fire large stones during a siege, were primarily designs of captured Greek weapons. Using loops of twisted animal tendon to generate energy, the ballistae worked much like the springs in giant mousetraps and could launch projectiles up to 457 meters away. Because it was light and accurate, these weapons could also be equipped with darts or large arrows and used to defeat enemy warriors (as an anti-personnel weapon). Ballistas were also used to hit small buildings during siege.

Onager - catapult

The Romans also invented their own siege engines called onagers (named after the wild donkey and its powerful kick) to throw large stones. Although they also used elastic animal sinew, onagers were much more powerful mini-catapults that were fired from a sling or bucket filled with round stones or flammable clay balls. They were much less accurate than ballistas, but more powerful, making them ideal for breaking down and setting fire to walls during a siege.

Concrete

When it comes to innovation in building materials, it's hard to beat liquid stone, which is lighter and stronger than regular stone. Today, concrete has become so integrated into our daily lives that it is easy to forget how revolutionary it is.

Roman concrete was a special mixture of crushed stone, lime, sand and pozzolan, volcanic ash. Not only could the mixture be poured into any mold you could build a wooden mold for, it was much, much stronger than any of its constituent parts. Although it was originally used by Roman architects to create strong bases for altars, starting in the 2nd century BC, the Romans began experimenting with concrete to create more free-standing forms. Their most famous concrete structure, the Pantheon, which after more than two thousand years is still the largest unreinforced concrete structure in the world.

The Pantheon, after more than two thousand years, still remains the largest unreinforced concrete structure in the world.

As we mentioned earlier, this was a major improvement on the old Etruscan and Greek rectangular styles of architecture, which required heavy walls and columns throughout. Moreover, concrete as a building material was cheap and fireproof. It could also dive underwater and was flexible enough to survive the earthquakes that periodically hit the volcanic Italian peninsula.

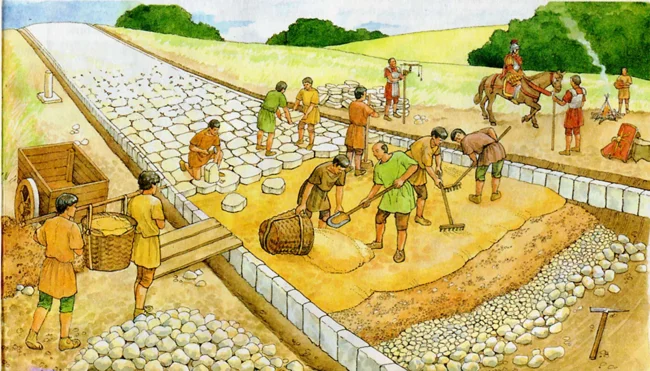

Roads

It is impossible to mention Roman engineering without talking about the roads, which were so well built that many of them are still in use today. Comparing our own paved roads to an ancient Roman road is like comparing a cheap watch to a Swiss version. They were strong and durable.

The best Roman roads were built in several stages. Workers first excavated about 0.9 meters into the area where the planned road would run. Wide, heavy stone blocks were then placed at the bottom of the trench, which were then covered with a layer of earth or gravel to provide drainage. Finally, the top layer was paved with slabs with a protrusion in the center to allow water to drain away. In general, Roman roads were about 0.9 meters thick and extremely resistant to the ravages of time.

Appian Way in ancient Rome

In typical Roman fashion, the Empire's engineers insisted on using primarily straight lines for their roads and sought to overcome obstacles rather than around them. If there was a forest, it was cut down. If there was a hill, they would tunnel through it. If there was a swamp, it was drained. Of course, the downside to this type of road construction is the sheer amount of labor required, but labor (in the form of thousands of slaves) was something the ancient Romans always had in abundance. By 200 AD, there were over 85,295 kilometers of major roads crossing the Roman Empire.

Sewerage

The great sewers of the Roman Empire are one of the strangest designs of engineering because they originally had a different function. It’s more likely not even an invention, but rather something that has developed over time. Sewers, as they are better known, were originally just canals built to drain some local swamps. Construction began around 600 BC, and over the next 700 hundred years more and more waterways were added. Since more canals were dug whenever it was deemed necessary, it is difficult to say when these sewers ceased to be drainage ditch and became actual sewers. Although the system was initially primitive, it spread like a weed, sinking its roots deeper and deeper into the city as it grew.

Great sewer in ancient Rome

Unfortunately, since it flows directly into the Tiber, the river is completely swollen with human waste. This is of course not an ideal situation, but with their aqueducts, the Romans did not need to use the Tiber for drinking or washing. They even had a goddess who looked after their system - Cloaquina, the Venus of the sewer.

Perhaps the most important and brilliant innovation of the Roman sewer system is the fact that it was (eventually) closed, reducing disease, odors and unpleasant sights. Any civilization can dig a ditch, but the Roman sewer system was so complex that Pliny the Elder even declared it a greater monument to human achievement than the pyramids.

Heated floors

Effectively controlling temperature in any building is one of the most difficult engineering problems humans have ever faced, but the Romans solved it—or at least nearly solved it. Based on an idea we still use today in the form of underfloor heating, hypocausts were a series of hollow clay columns placed every few feet under a raised floor, through which hot air and steam from a furnace in another room were forced.

Hypocaust

Unlike other, less advanced heating methods, the hypocaust neatly solved two problems that had always been associated with heating in the ancient world - smoke and fire. Fire was the only source of heat available, but it also had the unfortunate side effect of occasionally burning buildings down, and smoke from internal flames could be lethal in confined spaces. However, because the floor was raised in hypocaust conditions, the hot air from the furnace never came into contact with the room itself. Instead of entering the room, heated air was forced through hollow tiles in the walls. When he left the building, the clay tiles absorbed the heat, leaving the room itself heated and the Romans' feet warm.

Aqueduct

Along with roads, aqueducts are another engineering marvel for which the Romans are most famous. The peculiarity of aqueducts is that they are long. One of the difficulties of watering a large city was that, once the city reached a certain size, there was no way to get clean water anywhere nearby. And although Rome was on the Tiber, the river itself was polluted by another achievement of Roman engineering, which we discussed above - their sewage system.

Aqueduct in ancient Rome

To solve this problem, Roman engineers built aqueducts—networks of underground pipes, overhead water conduits, and elegant bridges designed to carry water into the city from the surrounding countryside. Once in Rome, water from the aqueducts was collected into cisterns and then poured into the fountains and public baths that the Romans loved.

Like their roads, the Roman aqueduct system was incredibly long and complex. Although the first aqueduct, built around 300 BC, was just under 18 km long, by the end of the third century AD there were 11 aqueducts in Rome, totaling over 400 km in length.

The power of water

Vitruvius, the godfather of Roman engineering, describes several technologies that the Romans used to supply water. By combining Greek technologies such as gearing and the water wheel, the Romans were able to develop advanced sawmills, mills and turbines.

Another Roman invention was the wheel, which was rotated by flowing (rather than falling) water, which made it possible to build floating water wheels to grind grain supplies. This came in handy during the siege of Rome in 537 AD, when the defending general Belisarius solved the problem of a Gothic siege cutting off food supplies by building several floating mills on the Tiber to keep the population supplied with bread.

Water-lifting mechanisms in ancient Rome

Ironically, archaeological evidence suggests that although the Romans had the technical knowledge necessary to create all sorts of water-powered devices, they rarely did so, preferring cheap and widely available slave labor. However, their water mill at Barbegal (in what is now France) was one of the largest industrial complexes in the ancient world before the Industrial Revolution, with 16 water wheels to grind flour for the surrounding communities.

Segmental arch

Like almost all of the engineering advances we've listed, the Romans didn't invent the arch, but they did improve on it. Arches existed for almost two thousand years before the Romans mastered the ability to build them. What the Roman engineers understood (quite brilliantly, as it turned out) was that arches did not have to be continuous; that is, they do not necessarily have to travel the required distance at one time. Instead of trying to overcome the gaps in one big jump, they can be broken up into several smaller sections. There was no need to turn the arch into a perfect semicircle if there were spacers under each section. This is where the segmental arch appeared.

Roman arch bridge

This new form of arch construction had two obvious advantages. First, because arches can be repeated rather than having one single span, the potential span distance for a bridge can be increased exponentially. Second, because less material was required, segmental arch bridges were more susceptible to the flow of water beneath them. Instead of forcing water through one small hole, water under the segmented lintels could flow freely, reducing both the risk of flooding and wear on the supports.

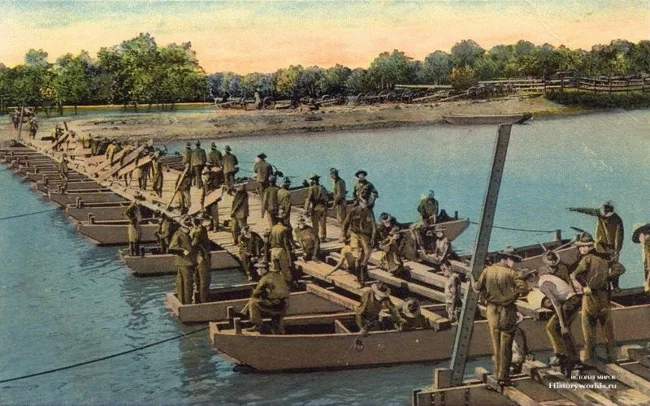

Pontoon bridges

Roman engineering was basically synonymous with military engineering. Those roads for which they are so famous were built not so much for everyday use (though they were certainly useful for that) but for legions to quickly march into the countryside, get into trouble spots and get out again. Roman-designed pontoon bridges, built mainly during wars, served the same purpose. In 55 BC. Julius Caesar built a pontoon bridge about 400 meters long to cross the Rhine River, which was traditionally considered beyond the reach of Roman power by the Germanic tribes.

Ancient Roman pontoon bridge

Caesar's Bridge over the Rhine was clever for several reasons. Building a bridge without draining water is notoriously difficult, and even more so in a military environment where construction must be constantly guarded, so engineers had to work quickly. Instead of driving the beams directly into the river, engineers drove the logs into the river bed at an angle against the current, giving the foundation extra strength. Protection piles were also driven upstream to intercept or slow down any potentially destructive logs that might float down the river. Finally, the beams were connected and a wooden bridge was built on top. In total, construction took only ten days, made full use of local lumber, and made clear to the local tribes the power of Rome: if Caesar wanted to cross the Rhine, he could do so.

There is also a possibly apocryphal story about Caligula's pontoon bridge, built across the sea between Baia and Puzzuoli, 4 kilometers long. Presumably, Caligula built the bridge because a soothsayer predicted that he had the same chance of becoming emperor as if he decided to cross the Bay of Bahia on a horse. Never one to show restraint, Caligula supposedly took this as a challenge and built the bridge anyway.