Thanks to modern technologies (radars, drones, satellite images), new opportunities have emerged to study the secrets of the past, from cities lost in the jungle or at the bottom of the ocean to ancient ruins buried under the thickness of the earth. Previously, people did not have such opportunities - hence the number of legends about distant lands and kingdoms that never existed in reality.

1. Kingdom of Prester John

Around the 12th century, Europeans heard rumors that somewhere in Asia there lived a Christian king who ruled an unnamed kingdom and fought the ever-growing threat of Islamic conquerors. His name is Prester John and he is supposedly a descendant of one of the three wise men who brought gifts to the baby Jesus.

It is not surprising that the European powers looked at Prester John as a possible ally, especially since all this happened during the first crusades. But, alas, attempts to find him or his kingdom were unsuccessful.

Somewhere in 1165, a letter began to circulate throughout Europe, allegedly written by Prester John. Today it has already been proven that it was a fake, but there is no answer to the question of who created it and for what purpose. The most plausible explanation suggests that this fake letter was clever propaganda to increase support for the Third Crusade. One way or another, the legend of Prester John lasted for almost 500 years. His kingdom was sought for a long time in Asia, and then in Africa (Ethiopia) - wherever Christian communities existed.

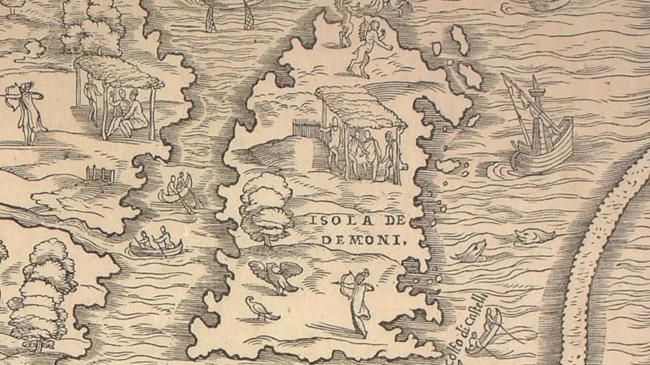

2. Island of Demons

Legend has it that around 1542, a French noblewoman named Marguerite de la Rocque set out on a journey led by her uncle, Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval, from France to the New World. During the trip, she had an affair with one of the sailors and became pregnant by him, which her uncle really did not like. To punish Marguerite, Roberval marooned her, her lover, and her maid Damien on an island known as the Isle of Demons. Most other ships stayed away from this landmass because they believed it was haunted by evil spirits. Many sailors have reported hearing strange noises whenever they get too close. Then Margarita had a child, who soon died. Her lover and maid also died, and Margarita had to survive alone, hunting wild animals. She lived alone on the island for about two years before being rescued by a passing ship and returned to France.

As for Demon Island, it simply disappeared from maps around the mid-17th century after being there for over a hundred years. There is definitely no island in the place where it was drawn on old maps. It is now theorized that this same Margarita (if she existed) is stranded on either Quirpon Island or Harrington Harbor off the northeast coast of Canada.

3. Bermeja Island

This is another ghost island with a similar premise - for hundreds of years people thought it was real, and it appeared on many 16th and 17th century Gulf of Mexico maps. Then, in the 18th century, cartographers stopped drawing it, so either something happened to Bermeja Island or it never existed.

But while most other ghost islands are simply considered curiosities of the past, Mexico is still trying to find Bermeja. Why? Because it costs a lot of money. This is the area of the Hoyos de Dona oil field. In 2009, the island's existence (or lack thereof) played a decisive role in negotiations over oil drilling rights between Mexico and the United States in the Gulf of Mexico. If the island actually existed, it would significantly expand the area of Mexico. There is even speculation that the US deliberately blew up the island to gain drilling rights.

4. Lyonesse (Lionesse)

Today Land's End (Land's End) in Cornwall is the westernmost point of England on the mainland. But it wasn’t always like this, according to legend. There was a time when there was a kingdom called Lyonesse, built on a piece of land that connected Land's End with the present Isles of Scilly in the Celtic Sea.

There were 140 churches in the kingdom, as well as a gigantic cathedral that stood on top of what is now called the Reef of the Seven Stones. But alas, the people of Liones committed an unspeakable sin against God, which was so terrible that the entire kingdom went under water in one night.

The charity English Heritage decided to test this myth and funded a study in 2009 called the Lyonesse Project. Researchers have discovered that thousands of years ago the Isles of Scilly were a single landmass. However, no lost kingdom was discovered.

5. Crocker Land

Crocker Land is an island that appeared on maps north of Canada's Ellesmere Island in the early 20th century. The existence of Crocker Land was recognized based on the testimony of one man, Arctic explorer Robert Peary, who claimed to have spotted the island during an unsuccessful expedition to the North Pole in 1906. He named it Crocker Land after one of his main patrons, George Crocker.

Perhaps Piri was sincerely mistaken in falling victim to the mirage known as Fata Morgana, or perhaps he simply wanted to extract more money from his patron for the next expedition. In any case, the existence of Crocker Land was important: it could be a decisive factor in determining who reached the North Pole first. In 1909, Peary claimed that he had accomplished this feat, but he had a rival, another explorer named Frederick Cook. He claimed to have reached the North Pole a year earlier.

Cook claimed that he had been to the place where Crocker Land should be and had not seen such an island. This meant that one of them was lying, and it was logical to assume that the one who lies about Crocker Land would also lie about his reaching the North Pole. In 1913, an independent expedition set out to search for the island. They found nothing, but they were still more inclined to believe Peary than Cook. Perhaps they were both lying about their achievements. However, it is still officially believed that Robert Peary was the first to reach the North Pole.

6. The Lost City of Z

Hidden somewhere in the Amazon jungle are abandoned ancient cities just waiting to be discovered. The British topographer and traveler Percy Harrison Fawcett was sure of this all his life. Based on some old documents and testimony from indigenous people, Fawcett became convinced that the ruins of an unknown civilization were hidden in the Brazilian jungles of Mato Grosso. He named the goal of his search as the Lost City of Z.

Unfortunately for Fawcett, the outbreak of World War I delayed his plans and he went to fight on the Western Front. But as soon as peace was declared, Fawcett organized an expedition to Brazil - it began in 1920 and was a complete failure. The traveler had to give up and return home because he fell ill with a fever. But he made several more attempts in subsequent years.

In 1925, Fawcett set off on another expedition, on which he took his son Jack and a family friend named Raleigh Rimell. All three disappeared into the jungle, never to be seen again. In the following decades, numerous expeditions tried to find out what happened to them. However, the fate of the explorers and the location of the Lost City of Z remain a mystery.

7. Sandy Island

As with Crocker Land, the existence of Sandy Island (or Sables in French) in French territorial waters in the South Pacific was initially accepted because it was reported by a reliable source. It was Captain James Cook and he charted the island in 1776 at the tip of New Caledonia. Then, a hundred years later, its discovery was officially confirmed by a whaling ship called Velocity. After this, there was no longer any reason to doubt its existence, and Sandy Island existed on maps for almost a century and a half, even ending up in Google Earth.

It was only in 2012 that an Australian research ship convincingly proved that this island does not exist. But what's really strange is that the French knew for decades that the island wasn't real. They first listed it as ED, meaning "existence doubtful", and then removed it completely from all their hydrographic charts in 1974. But it looks like they forgot to tell everyone else.

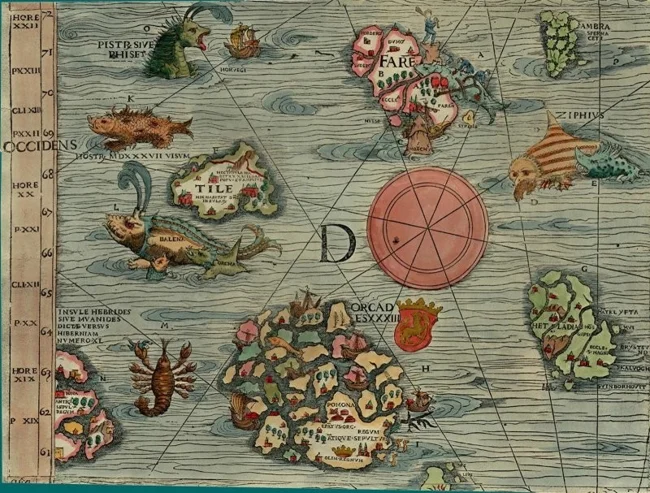

8. Thule Island

The Lost Island of Thule (Thula) is one of the oldest mythical places, first mentioned by the ancient Greeks, along with Atlantis. However, unlike Atlantis, Thule does not have a colorful history of floods and destruction caused by the wrath of the gods. According to the Greeks and Romans, it was simply the northernmost site they knew of after it was first described by the Greek navigator Pytheas in the late 4th century BC.

Pytheas sailed from Marseilles and traveled north past the British Isles into uncharted territory until he reached Thule, a land “in which land, sea, and all together are suspended, and this mixture ... is impassable either on foot or by ship.” Returning home, Pytheas wrote a treatise On the Ocean, one of the most significant travel journals of the ancient world. He may even have given precise directions on how to get to Thule. However, his work was lost when the Library of Alexandria burned down, and all we have left are a few scraps of information referenced in other books.

Later sources reported strange blue-skinned warriors of Thule Island, similar to Vikings. Legends told that these people wage an eternal war against the underground gnomes. And everything on this island is shrouded in fog. In the Middle Ages, Thule was often identified with Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Shetland, Orkney and the Hebrides, parts of Britain or Scandinavia. The expression Ultima Thule means “very far”, “end of the world”, “far limit”, “far task”.

9. Paititi

Legend has it that when the Spanish conquistadors sacked the Inca capital of Cusco, they found only a small portion of the giant Inca treasure. They say the Incas managed to transport their reserves of gold and silver from the capital to the secret city of Paititi, hidden deep in the jungle east of the Andes.

But soon after, the Inca Empire fell to the Spanish and the site of Paititi was lost forever. Since then, countless archaeologists, explorers and treasure hunters have risked and even sacrificed their lives in search of this lost city. Expeditions do not stop to this day. One of the last took place just ten years ago.

10. Zerzura

In 1843, British Egyptologist John Gardner Wilkinson wrote: “Five or six days west of the Farafra road there is another oasis called Wadi Zerzura, about the size of the Oasis of Perwa, abounding in palm trees, springs and some ruins of unknown age. It was discovered about twenty years ago by an Arab looking for a lost camel. Based on the footprints of people and sheep, he suggested that the oasis was inhabited.”

This is where the search for the lost oasis city of Zerzura began. Wilkinson's story prompted many explorers to travel deep into the Sahara in search of a mythical place. The most famous was the 1929 expedition led by László Almasy, a Hungarian pilot who became the inspiration for the main character in the film The English Patient. Almásy also led an expedition in 1932 and discovered Wadi Tal, supposedly one of the three valleys of Zerzura. The other two valleys were discovered by another expedition led by the Clayton couple, as well as an aerial survey by Almasy's colleagues. It is unclear whether these finds were actually the lost city of Zerzuza.

0 comments